WWI antiseptic could fight 21st century viral infections

By Hudson Institute communications. Reviewed by Professor Michael Gantier

Melbourne researchers have shown that a century-old topical antiseptic used to treat wounds and ‘sleeping sickness’ in Australian soldiers in World War One could activate the immune system to protect against viral infection, and may prove key in the fight against antibiotic resistance.

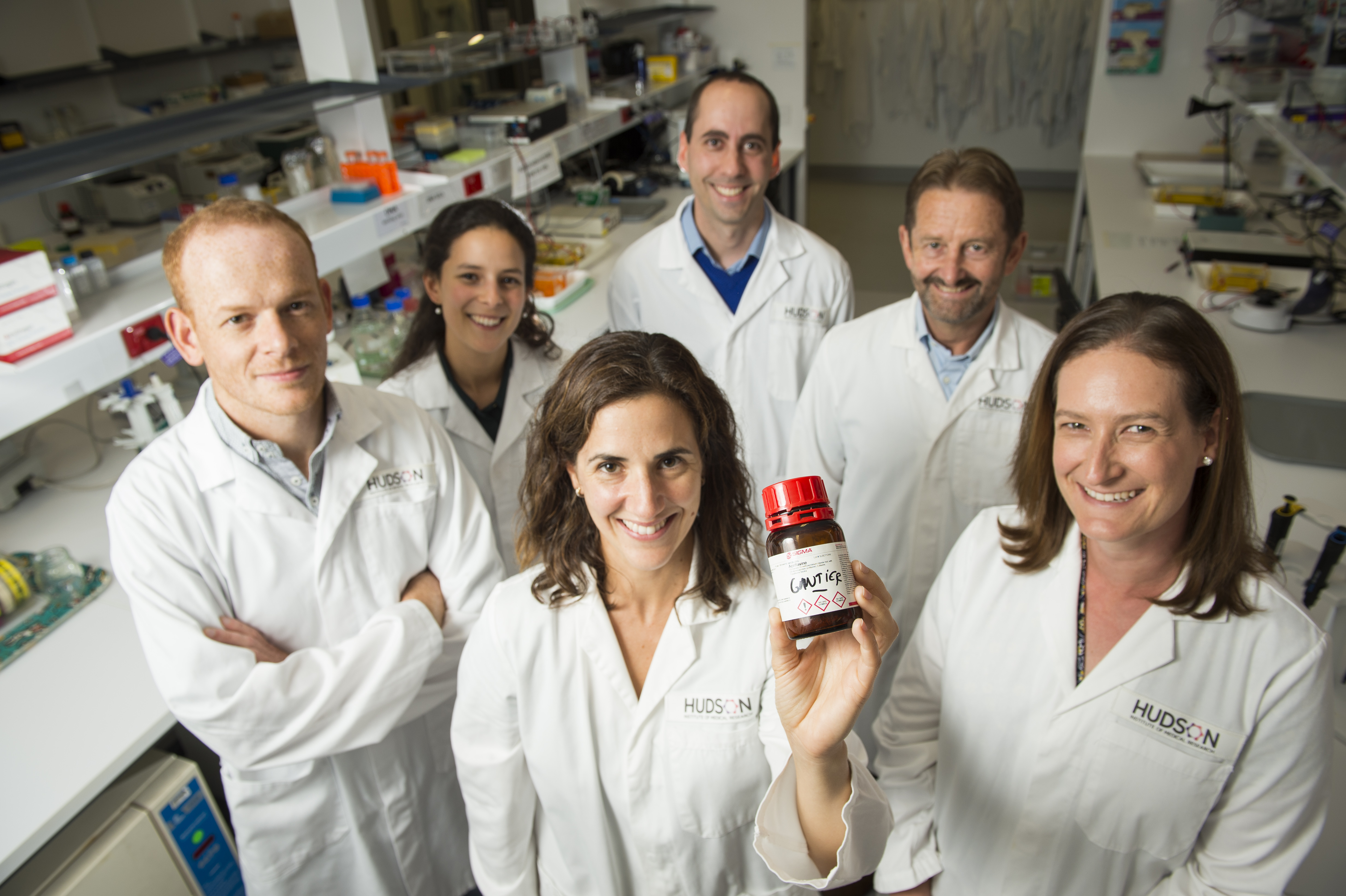

A study by the team of scientists at Hudson Institute of Medical Research in Clayton, has shown that a century-old antiseptic called Acriflavine, made from coal tar, protects against the common cold. The findings of the study, led by Dr Michael Gantier and Dr Genevieve Pepin in the Nucleic Acids and Innate Immunity Group at Hudson Institute, have just been published in the prestigious journal, Nucleic Acids Research.

Acriflavine triggers powerful immune response

The team believes the way Acriflavine activates the immune system could also offer a useful tool in the fight against superbug resistance, and viral pandemics.

In the study, the team showed that pre-treating human lung cells with Acriflavine protected the cells against rhinovirus infection (the common cold) by triggering an anti-viral immune response.

Dr Gantier, head of the Research Group in Hudson Institute’s Centre for Innate Immunity and Infectious Diseases, says Acriflavine was used to treat everything from gonorrhoea to urinary infections prior to World War Two, but a whole picture of its mechanism of action has evaded scientists – until now.

“Acriflavine was heavily used during World War One as a topical antiseptic to treat wounds. Early scientific literature notes its antibacterial qualities in test tubes, but its very effective action on the skin has never been fully defined,” Dr Gantier said.

“We have shown for the first time that Acriflavine binding to cellular DNA could activate the host immune system, unleashing a powerful immune response on a potentially broad range of bacteria.

Double punch

“The effect is two-fold – Acriflavine directly affects the bacteria, and then you get the activation of the immune system through the ‘STING’ pathway, which helps to clear the infection,” he said.

Acriflavine (also known as Trypaflavine) was first identified as an antiseptic by German scientists in 1912[i]. It was used by soldiers in the First World War to treat wounds and kill parasites that cause sleeping sickness. Australia’s volunteer nurses in the Second World War also had acriflavine in their kits[ii].

Acriflavine used before penicillin

Dr Genevieve Pepin, first author on the paper, says Acriflavine could one day offer a safeguard against drug resistance, and could be used during a viral outbreak to trigger a baseline immune response to an infection, such as SARS or influenza, in at-risk groups.

“Acriflavine was used in the first half of the 20th century as a topical antibacterial, before being supplanted by penicillin. Now, antibiotic resistant superbugs are a growing threat to human health,” Dr Pepin said.

“Our study indicates that Acriflavine stimulates the host immune system, rather than simply killing bacteria, suggesting it wouldn’t be as likely to drive mutations in bacteria – showing a safeguard against resistance and a potential alternative to current antibacterial drugs,” she said.

Potential to treat viral and bacterial infections

Next, the team will use pre-clinical models to test how well Acriflavine mobilises the immune system in more virulent strains of infection.

Dr Gantier says Acriflavine, a drug that has largely been out of use for the last 50 years, is showing strong potential against viral and bacterial infections and their newest challenges in the 21st century.

[i] https://www.britannica.com/science/acriflavine

[ii] https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/REL31069/

Journal | Nucleic Acids Research

Title | Activation of cGAS-dependent antiviral responses by DNA intercalating agents

View publication | https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw878

In this article

About Hudson Institute

Hudson Institute’ s research programs deliver in three areas of medical need – inflammation, cancer, women’s and newborn health. More

Hudson News

Get the inside view on discoveries and patient stories

“Thank you Hudson Institute researchers. Your work brings such hope to all women with ovarian cancer knowing that potentially women in the future won't have to go through what we have!”